Este artículo trata de servir como introducción a la gestión de memoria en .Net, los límites que el Runtime y la plataforma establecen para cada proceso, así como algunos Tips para lidiar con los problemas a los que nos enfrentamos al acercarnos a esos límites.

Memoria disponible por proceso

Como muchos de vosotros sabéis, por mucha memoria RAM que tenga instalada un ordenador, existen varias barreras impuestas a la cantidad de memoria usable en nuestras aplicaciones.

Por ejemplo, en un sistema de 32 bits no se pueden instalar más de 4GB de memoria física, evidentemente, porque 2^32 (dos elevado a 32) nos proporciona un espacio de direcciones con 4.294.967.296 entradas distintas (4GB). Pero incluso cuando el sistema cuente con 4GB de memoria física, nuestras aplicaciones se encontrarán con una barrera de 2GB impuesta por el sistema.

En estos entornos de 32 bits, cada proceso puede acceder a un espacio de direcciones de 2GB como máximo, porque el sistema se reserva los otros 2 para las aplicaciones que corren en modo Kernel (aplicaciones del sistema). Este comportamiento por defecto puede cambiarse mediante el uso del flag “/3gb” en el boot.ini del sistema, haciendo que Windows reserve 3GB para las aplicaciones que corren en Modo Usuario y 1GB de memoria para el Kernel.

Aún así, el límite por proceso permanecerá en 2GB, a no ser que explícitamente activemos un flag determinado (IMAGE_FILE_LARGE_ADDRESS_AWARE) en la cabecera de la aplicación. A esta combinación de flags en sistemas x86 se le denomina comúnmente: 4GT (4 GigaByte Tuning).

En sistemas de 64 bits sucede algo parecido. Aunque no tienen la misma limitación en cuanto a memoria física disponible, ni la impuesta por la reserva de direcciones para el kernel (y por lo tanto el flag /3gb no aplica en estos casos), el sistema también establece un límite por defecto de 2 GB para cada proceso, a no ser que se active el mismo flag en la cabecera de la aplicación (IMAGE_FILE_LARGE_ADDRESS_AWARE).

Activando el flag: IMAGE_FILE_LARGE_ADDRESS_AWARE

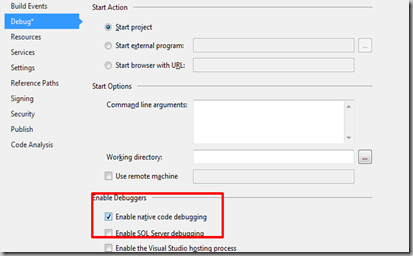

- En el caso de aplicaciones nativas (C++), establecer dicho flag es fácil, ya que basta con añadir el parámetro /LARGEADDRESSAWARE a los parámetros del Linker dentro de Visual Studio.

- En el caso de aplicaciones .Net:

- Si están compiladas para 64bits, este flag estará activado por defecto, por lo que podrán acceder a un espacio de direcciones de 8 TB (dependiendo del S.O.)

- Si están compiladas para 32bits, el entorno de Visual Studio no nos ofrece ninguna opción para activar dicho flag, por lo que tendremos que hacerlo con la utilidad EditBin.exe, distribuida con Visual Studio, la cual modificará el ejecutable de nuestra aplicación (activándole dicho flag).

La siguiente tabla, obtenida de esta página, muestra de forma resumida los límites en el espacio de direcciones de la memoria virtual, en función de la plataforma y del tipo de aplicación que estemos desarrollando:

Esta página tiene mucha más información sobre los límites de memoria según las versiones del S.O.

Los límites del sistema, más cerca de lo que crees

Hoy día, la memoria es barata, pero como ya se ha explicado en el apartado anterior, hay un buen número de casos en los que, por mucha memoria que instalemos en el PC, nuestro proceso solo podrá acceder a 2GB de la misma.

Además de esto, si vuestra aplicación está desarrollada en .Net, os encontraréis con que el propio Runtime introduce un overhead importante en cuestiones de memoria (suele decirse que está en torno a los 600-800 MB), por lo que en una aplicación corriente, es usual empezar a encontrar OutOfMemoryExceptions alrededor de los 1.3 GB de memoria usados. En este blog se discute el tema.

Por lo tanto, si no estamos en uno de esos casos en los que podemos direccionar más de 2GB, y además desarrollamos en .Net, independientemente de la memoria física instalada en el sistema nuestro límite real estará en torno a 1.3 GB de memoria RAM.

Para el 99% de las aplicaciones diarias, es más que suficiente, pero otras que requieren cálculos masivos, o que se relacionan con bases de datos, muy frecuentemente superarán ese límite.

Y lo que es peor…

Para complicar todavía más el asunto, una cosa es tener memoria disponible, y otra muy distinta es tener bloques de memoria contiguos disponibles.

Como todos sabéis, fruto de la gestión que el Sistema Operativo hace de la memoria, de técnicas como la Paginación, y de la creación y destrucción de objetos, la memoria poco a poco va quedando fragmentada. Esto quiere decir que, aunque tengamos suficiente memoria disponible, esta puede estar dividida en muchos bloques pequeños, en lugar de un único hueco con todo el tamaño disponible.

Los Sistemas Operativos modernos, y la propia plataforma .Net, tratan de evitar esto con técnicas de Compactación, y aunque reducen notablemente el problema, no lo eliminan por completo. Este completo artículo describe en detalle la gestión de memoria del Garbage Collector de .Net, y la labor de compactación que realiza.

¿En qué afecta la fragmentación? En mucho, ya que si vuestra aplicación necesita reservar un Array contiguo de 10 MB, y aunque todavía haya 1GB de memoria disponible, si la memoria está muy fragmentada y el sistema no es capaz de encontrar un bloque contiguo de ese tamaño, obtendremos un OutOfMemoryException.

En .Net, la fragmentación y compactación de objetos en memoria guarda una estrecha relación con el tamaño de éstos. Por eso, el siguiente apartado hablará un poco sobre este tema.

Grandes objetos en memoria

A la hora de reservar memoria para un único objeto, la plataforma .Net establece ciertos límites. Por ejemplo, en las versiones de .Net 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 3.5 y 4.0, ese límite es de 2GB. Tanto para plataformas x86 como x64, ningún objeto único puede ser mayor de ese tamaño. Es así de simple. Únicamente a partir de .Net 4.5 este límite puede ser excedido (en procesos x64 exclusivamente). Aunque sinceramente, salvo rarísimas excepciones, si necesitas reservar más de 2GB de memoria para un único objeto, quizá deberías replantearte el diseño de tu aplicación.

En el mundo .Net, el Garbage Collector clasifica a los objetos en dos tipos: objetos grandes y objetos pequeños. Es una división bastante gruesa, la verdad, pero es así. ¿Qué considera .Net como un objeto pequeño? Todo aquel que ocupe menos de 85000 bytes.

Cuando el CLR de .Net es cargado, se reservan dos porciones de memoria diferentes: un Heap para los objetos pequeños (también llamado SOH, o Small Objects Heap), y otra para los objetos grandes (también llamado LOH, o Large Object Heap), y cada tipo de objeto se almacena en su Heap correspondiente.

¿En qué afecta todo esto al tema que estamos tratando? Sencillo, compactar objetos grandes es costoso, y a día de hoy, simplemente no se hace. Los objetos considerados “Grandes”, y que se introducen en el LOH, no se compactan (aunque el equipo de desarrollo advierte que pueden hacerlo algún día). Como mucho, cuando dos objetos grandes adyacentes son liberados, se fusionan en un único espacio de memoria disponible, pero ningún objeto es “movido” para realizar tareas de compactación.

Este fantástico artículo contiene muchísima más información acerca del LOH y su funcionamiento.

Arrays C# en los límites de la memoria

En C#, los Arrays Simples (de una dimensión) son una de las formas más comunes de consumir memoria, y debes saber que el CLR los reserva siempre como bloques continuos de memoria. Es decir, cuando instanciamos un objeto de tipo byte[1024], estamos solicitando al sistema un único bloque continuo de 1KB, y se generará un OutOfMemoryException si no encuentra ningún hueco contiguo de ese tamaño.

Cuando es necesario utilizar un Array de más de una dimensión, C# nos ofrece distintas opciones:

Arrays anidados, o arrays de arrays

Declarados como byte[][], suponen el método clásico de implementar arrays multi-dimensionales. De hecho, en lenguages como C++, es el único tipo de array multi-dimensional soportado de forma nativa.

En lo relativo a memoria, se comportan como un array simple (un único bloque de memoria), en el que cada elemento es otro array simple (esta vez del tipo declarado, y que también es un bloque único en memoria, pero distinto a los demás). Por lo tanto, en lo que a bloques de memoria se refiere, un array de tipo byte[1024][1024], utilizará 1024 bloques de memoria distintos (cada uno de 1024 bytes).

Arrays Multi-Dimensionales

C# introduce un nuevo tipo de Arrays, soportado de forma nativa: los arrays multi-dimensionales. En el caso de 2 dimensiones, se declaran como byte[,].

Aunque son muy cómodos de utilizar (disponen entre otras cosas de métodos como GetLength, para saber el tamaño de una dimensión), y su instanciación es más sencilla, su representación en memoria es diferente a la de los arrays anidados. Éstos se almacenan como un único bloque de memoria, del tamaño total del array.

En el siguiente apartado estableceremos una comparativa entre ambos tipos:

Comparativa: [,] vs [][]

El array 2D [,] (se almacena en un solo bloque):

Ventajas:

- Utiliza menos memoria total (no tiene que almacenar las referencias a los n arrays simples)

- Su creación es más rápida: reservar un bloque grande de memoria para para un solo objeto es más rápido que reservar bloques más pequeños para muchos objetos.

- Su instanciación es más sencilla: una sola línea basta (new byte[128,128]).

- Proporciona métodos útiles, como GetLength, y su uso es más claro y limpio.

Inconvenientes:

- Encontrar un solo bloque de memoria continuo para el array puede ser un problema, si éste es muy grande o nos encontramos cerca del limite de RAM.

- El acceso a los elementos del array es más lento que en arrays anidados (ver abajo)

El array anidado [][] (que se almacena en N bloques):

Ventajas:

- Es más fácil encontrar memoria disponible para el array, ya que requiere de n bloques de tamaño más pequeño, lo cual debido a la fragmentación, suele ser más probable que encontrar un único bloque más grande.

- El acceso a los elementos del array es más rápido que en los arrays 2D, gracias a las optimizaciones del compilador para manejar arrays simples (en definitiva, un array de arrays se compone de muchos arrays 1D).

Inconvenientes:

- Utiliza más memoria total (tiene que almacenar las referencias a los n arrays simples)

- Su creación es más lenta, ya que hay que reservar N bloques de memoria, en lugar de uno solo.

- Su instanciación es un poco más molesta, ya que hay que recorrer el array instanciando cada uno de sus elementos (ver Tip más abajo).

- No proporciona los métodos disponibles en los arrays 2D, y su uso puede ser un poco más confuso.

Este blog explica muy bien esta comparativa.

Conclusión

Cada usuario debe escoger el tipo de array que más le convenga en función de su experiencia y el contexto concreto en el que esté. No obstante, un desarrollador que habitualmente utilice gran cantidad de memoria, y preocupado por el rendimiento, tenderá a escoger siempre arrays anidados (o arrays de arrays [][]).

Tip: código generico para instanciar arrays anidados

Dado que instanciar un array de arrays es un poco molesto y repetitivo (y ya dijimos aqui que no conviene duplicar código), el siguiente método genérico se encargará de esa tarea por vosotros:

public static T[][] Allocate2DArray<T>(int pWidth, int pHeight)

{

T[][] ret = new T[pWidth][];

for (int i = 0; i < pHeight; i++)

ret[i] = new T[pHeight];

return ret;

}

Espero que os Sirva !!!